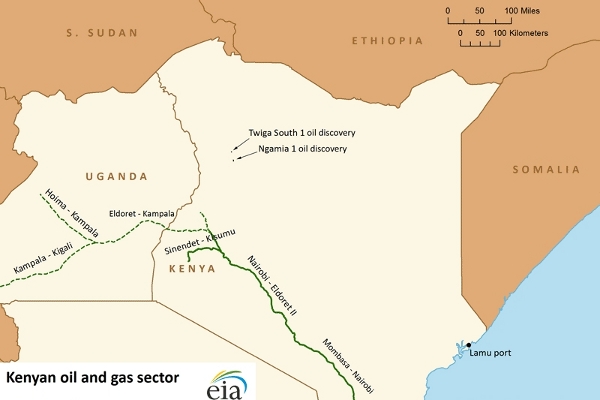

Around midday on Friday, February 1, 2013, a significant meeting took place at the Ministry of Energy offices at Amber House, Kampala Road. The names of the companies vying for the construction of the Kenya-Uganda petroleum pipeline from Eldoret to Kampala were unveiled.

With that, a vital topic was reawakened: the geopolitics that tend to haunt regional projects, such as this particular one where huge sums of money are at stake.

When it comes to undertaking such projects, the 14 companies that have shown interest in the pipeline will have to grapple with one thing though: Kenya and Uganda�s troubled history.

Officials from the two countries have mastered the art of exploiting photo opportunities when publicly discussing master plans of regional projects, but behind closed doors, such ventures are up against fat egos and political chicanery.

There are at least five examples that support this. Let�s start with this very pipeline project. From the time Tamoil won the original bid to build this pipeline in 2007, it was a case of pacing up and down by the Libyan firm as it sought to get its paperwork in order, as both governments had demanded. Amidst this though, top Libyan officials frequently flew in from Tripoli to ask for a quick start to the venture.

To be fair, there were claims that Tamoil had won the bid under dubious means. We can only hope that both Kenya and Uganda did their homework before handing Tamoil the contract.

What became a point of frustration for Tamoil was the promise by both Kenya and Uganda to offer land as part of their contribution in the 25% stake they held in the project. That land was never found. And when the government in Tripoli fell in 2011, Tamoil�s plans went with it.

There were accusations that the pipeline project was delayed because it would deny Kenya substantial revenue from the fuel tracks heading to Uganda. It is part of the wider speculation.

The Mombasa port forms the second case in point. Ugandans importing stuff through Mombasa port continue to complain about the over-congestion there. It�s a complaint that has been around for quite some time, but whose solution remains elusive.

The Mombasa port is at the centre of Uganda�s economy � over 90% of Uganda�s imports come through the port. But there is hardly a month that passes by without hearing a complaint about the congestion at there that has hampered many a Ugandan business.

To lessen the clogging up at Mombasa, a suggestion to build an inland port at Tororo was fronted sometime around 2005. This is my third example by the way.

The sketchy idea about the inland port was that goods would quickly pass through Mombasa, straight to Tororo.

What happened? You guessed right � the businessmen from both countries pulled out the swords, a point of contention being whether the firm should get a grace period � in the form of a monopoly � to recoup its investments. The project was dead and buried before it could even take off.

The fourth point comes in the form of the Kenya Uganda railway line. Shareholder disputes and a maverick of a businessman in the form of South Africa�s Roy Puffet conspired to make the Kenya-Uganda railway project a classic example of shady dealings and boardroom shenanigans.

For more than four years, Puffet managed to confuse both governments that work was about to take off, flagging off operations that would barely see the second week. In the end, Puffet sold his stake in Sheltam, the biggest shareholder in the project then, and walked away with quite a handsome bounty. We still do not have a functioning railway line for the region at present.

The oil refinery makes my fifth and last illustration. In 2008, two years after making its first commercial oil discovery, it was recommended that all the East African states enter into a joint venture to build a refinery. The plan was to have a 40% – 60% share structure in favour of the private investor. The East African governments would take up the 40% stake. The plan was to have one refinery in Uganda.

It sounded like a good plan until Kenya came close to striking oil. The plan is now discussed in hush tones. Recently, Eriya Kategeya, Uganda�s Minister for East African Affairs wrote to his counterparts about showing more commitment to the refinery. For now, it is a safe bet that the regional countries will not take part in this scheme.

Uganda will have to go at it alone, like a lone ranger in the wild, and try to find money and a partner for the refinery.

All said and done, there is a strong need why the petroleum pipeline deal should work out, if for anything else to show the world that East Africa can collaborate on a trans-boundary project.

Of course, there is a clique of businessmen who will get a larger slice of the �professional fees.� And of course, some mistakes will be made along the way.

But there is no doubt that such regional projects will promote more collaboration � the money and jobs at stake are good starting points to promote teamwork.

For once, a regional project will see both Kenya and Uganda feeling the pain when we get our economics and politics wrong. This is a kind of project where East Africa will finally announce its entrance as a powerful and organized economic bloc, and attract more investors.